Remberto Nolasco

Edgardo Mira

El Salvador has been historically characterized as a country with an axis of accumulation oriented towards agriculture, based on exporting a single crop, initially indigo. Then over the course of the 19th century, coffee was introduced, and then in the 20th, this was complemented by the production of cotton and sugarcane. In the country’s economic structure, these three crops are considered traditional exports, although cotton stopped being produced or exported after the 1980s.

The agricultural economy of El Salvador has been structured around the hacienda1 system since the Colonial Era, based on a significant concentration of land. Some 73% of land passed through the hands of 5.6% of owners, while 50% of the less-privileged population had to content itself with 3.4% of the communal land for production of food and cash crops, in addition to the forced relocation of indigenous workers by the colonial establishment.

During the hegemony of indigo production as the engine of capitalist accumulation (1878-79), farmworkers’ situations allowed for the production of food crops for self-consumption on communal lands; this allowed them to supplement that part of their food supply that was not covered by their poor wages.

However, the introduction of coffee (1850) was accompanied by the expropriation of communal lands (1881-82) and a greater proletarianization of the workforce as a consequence of the lack of land available for self-consumption. This led to the farmers, in order to protect themselves from having their lands plundered, being forced to sell their labor to the owners of large haciendas and, as a consequence, becoming dependent on wages.

After the expropriation of common lands to be used for coffee, there came the conditions that slowly increased vulnerability to natural threats, as the amount of agricultural land increased towards the mountains and changed the forested parts of the country. The disappearance of common property to make way for coffee growing involved expelling farmworkers from the best land.

Since 1860, the agro-exporting model based on growing indigo incited greater degredation of these lands by accelerating erosion and causing more flods and droughts. With the loss of communal lands, large segments of the population had to use land not fit for purpose to grow food, and to settle in higher-risk areas or concentrate in urban centers.

It is worth noting that, although coffee cultivation has made up the majority of El Salvador’s economic structure, after the 1950s, growing cotton (a crop that, together with sugar, formed a part of a strategy of diversification for export in that period) was also an agent of population removal and exploitation of the last agricultural frontiers.

The cultivation of cotton imposed new pressure on the deterioration of the environment and the changes in property ownership; however, this crop experienced a significant decline in the 1960s. We observe that in 1960-61, 58,165 hectares were cultivated and 114,136 hectares in 1963-64 when the decrease in area devoted to cotton began, a process that accelerated during the 1980s due to, on the one hand, an increase in imports from the United States and on the other, the civil war that broke out during those years.

The “agrarian modernization” of the 1950s, which basically consistent in expanding cotton growing and then that of sugarcane, completed the trend towards proletarianization of the rural workforce and monetization of lease-holding relationships. As a result, a growing proportion of the rural population began to depend directly and exclusively on salaried employment.

At the same time came the model of Industrialization through Substitution of Imports (ISI), which affected the agro-export model by creating a contradictory process in the sense of pushing for rural development based on crop diversity focused on the exterior on the one hand versus the pressures of the ISI on the other. This saw an increase in the demand for workers that was satisfied by the surplus of the rural workforce, which in turn caused increased migration from the fields to the cities.

This process of “agrarian modernization” or “green revolution” pushed forward during the 1960s sought diversification in terms of crops, and promoted various programs designed to increase agricultural production, primarily of foodstuffs. To this end, there began the large-scale use of fertilizers, improved seeds, pesticides, monocultures, irrigation, etc., which succeeding in significantly increasing the production of basic grains. However, this also meant an increase in dependence on imported agrichemicals, which in turn severely impacted agricultural diversity, above all in terms of native or Mesoamerican crops. For examples, of six varieties of maize, some parts of the country only grow two, predominantly a hybrid; the same thing occurred with beans, from ten varieties to three (those the most commercial), and with fruts (annona, star apple, sincuya, cocoa, etc.) that have been replaced by fruits from other regions.

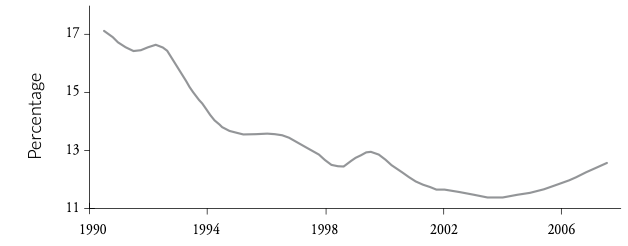

Nonetheless, despite the green revolution, the agricultural sector began to lose its importance in the country’s economic structure, which began to be reconfigured at the end of the 1960s with the implementation of an import-substitution model, worsened by armed conflict, to create conditions such that in the context of the implementation of neoliberalism, there would be a period of outsourcing after the beginning of the 1990s, years during which the agriculatural sector ceased to be one of the most dynamic in the Salvadoran economy. As can be seen in table 3.1 below, agriculture in 1970 was 18.7% of GDP and in 2008 was barely 13 percent.

Table 3.1. Change in GDP in El Salvador

Structure of the economy (percentage of GDP)

| 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 18.70 | 38.00 | 17.10 | 13.00 |

| Industry | 32.60 | 21.90 | 26.20 | 27.40 |

| Services | 49.80 | 40.10 | 56.60 | 59.60 |

The above is also confirmed by the levels of foreign currency from exports:

Until the end of the 1970s the economy depended for its functioning on the foreign currency coming from traditional agro-exports (coffee, cotton, sugarcane, shrimp), to the degree that of the total foreign currency income generated by the main sectors, 80% came from traditional agro-exports in 1978. By 1996, agro-exports generated less than in 1978, and its share of the total from the main sectors had reduced to 21%.2

As has been shown, after the 1990s there was a decline in the relative importance of the agricultural sector (table 3.1 and figure 3.1). In this decade in El Salvador, changes were put in motion to the economic structure in order to adapt to the demands of global capitalism, and a historically agrarian economy was reconfigured into an economy with an agricultural sector that was entirely broken up and in a state of permanent crisis.

At the same time, the socio-political structure of El Salvador, as Rubén explained, could be described “as the sum of oligarchic interests based on an integral concentration of economic control in the agricultural, commercial, agro-industrial, and manufacturing sectors. The primary industries are at the same time huge landholders, acquiring a substantial part of their income from agriculture” [citation omitted].

Finally, the implentation of a neoliberal dimension, which contributes to the insertion of El Salvador into the new global economy characterized by globalization, the primacy of the market, and as a consequence, the abolition of secional policies, did not allow true development in the country, which ##### Table 3.1. Change in GDP in El Salvadorgenerates–as has been said–a process of migration, first from the field to the city and then abroad, mainly to the United States, in search of the “American dream,” which in turn set up a new way of surviving, which became the lifeline for the Salvadoran economy through the present: remittences from abroad.

As found by Argueta [citation omitted], remittences by Salvadorans living abroad, which passed 12.2% of the GDP in 1997 and 14.1% in 2003, remain the “most important life preserver for the country’s economy, and also for dollarization. For example, they are equivalent to 67.8% of exports.”

Ownership and Uses of the Land

As shown by the IV Agricultural Census (2009), the potential natural resources for agriculture in El Salvador is 2.1 million hectares, of which 55% are being used for productive agriculture, essential grasses (22.5%), permanent grasses (5.8%), reflecting pools (0.1%), fallow or resting (6.4%), buildings (1.6%), not appropriate for agriculture (2.1%), and forest (47%).

The data regarding land ownership warrant special consideration. According to the Agricultural Census in 1971, there were 270,868 agricultural producers, of which 92.5% used 27.1% of the ariable land, these being considered mini-farms. At the other extreme are 1,941 producers, which is to say that 0.7% used a total of 561,518 hectares, which represented 38.7% of the ariable land; in this group of large-scale users, more than 202 were greater than 500 hectares, possessing a total of 218,641 hectares, that is 15% of usable land. There were only 15 possessions of more than 2,500 hectares, thus it is obvious that “these agricultural producers bought up the best lands for the three main agricultural exports: coffee in the highlands, sugarcane and cotton in the coastal plains and valleys” [citation omitted].

In the present, land ownership remains in the same condition, albeit with certain changes from phases I and III of the agrarian reforms, a program of land transfers resulting from the Peace Accords and the constitutional limitation on properties of more than 245 hectares, although this last has been avoided by some landowners by “dividing” lands beyond this amount among family members, thus keeping some plots their original size.

As shown by table 3.2, it may be seen that the portion of the population that possesses up to four blocks3 of land contains 225,727 producers, representing 88.6% of the total. They are considered mini-groups, with resources that are structurally incapable of producing enough to escape from poverty.

At the other extreme is the stratum of properties of more than 20 blocks, of which there are 20,463 producers, or 7.6%, confirming that a small number of producers own most of the ariable land. This is confirmed by Arias [citation omitted], who made a study on land concentration in El Salvador [in 2009], and who found that 75.3% of the land (1,335,166 hectares) is controled by 7.6% of producers with more than 14 hectares. This estimate clearly demonstrates the problem of land concentration, which remains serious and worsening in El Salvador.

In terms of the use of land for agriculture, this is measured at 1,619,930 hectares, of which almost 23.5% are used for the production of grains, primarily maze and beans, which are fundamental to the Salvadoran diet. Meanwhile, for the production of coffee and sugarcane, which are the traditional export crops, a total of 310,123 blocks are in use, which represents 13.4% of the lands used for agricultural activities (table 3.3).

The negative impact on the quality of farmland has been attributed to the uses and ownership of the land, which has mainly affected small farms, who grow most of their basic grains on land with questionable quality, mainly classes V, VI, and VII. They also make extensive use of agrochemicals which nonetheless do not help in obtaining better harvests, resulting in insufficient income for them to invest in conservation and the deterioration that results.

Table 3.2. Agricultural producers by area worked (in hectares) per department (2007)

| Department | Total | Less than 0.7 | 0.7 to 1.4 | 2.1 to 2.8 | 3.5 to 7 | 7.7 to 14 | More than 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Producers | 266,613 | 108,522 | 99,049 | 18,156 | 14,412 | 4,939 | 20,463 |

| Ahuachapán | 19,102 | 8,509 | 7,028 | 1,298 | 604 | 73 | 1,590 |

| Santa Ana | 25,155 | 8,599 | 11,209 | 1,806 | 1,806 | 519 | 1,214 |

| Sonsonate | 12,078 | 5,944 | 2,794 | 724 | 234 | 631 | 1,751 |

| Chalatenango | 16,561 | 6,399 | 5,623 | 782 | 1,551 | 587 | 1,619 |

| San Salvador | 19,365 | 8,155 | 7,055 | 516 | 1,532 | 340 | 1,767 |

| La Libertad | 14,273 | 7,257 | 4,508 | 749 | 150 | 121 | 1,488 |

| Cuscatlán | 16,370 | 5,691 | 7,343 | 1,304 | 1,012 | – | 1,020 |

| La Paz | 15,589 | 8,405 | 4,602 | 574 | 848 | 74 | 1,356 |

| Cabañas | 15,397 | 5,969 | 6,421 | 931 | 1,034 | 243 | 799 |

| San Vicente | 14,197 | 6,213 | 5,488 | 1,238 | 484 | 108 | 666 |

| Usulután | 20,537 | 6,279 | 8,934 | 1,345 | 1,322 | 304 | 2,353 |

| San Miguel | 31,896 | 12,299 | 11,804 | 2,890 | 1,366 | 1,114 | 2,423 |

| Morazán | 21,330 | 10,086 | 6,804 | 2,008 | 1,330 | 316 | 786 |

| La Unión | 23,393 | 8,717 | 9,436 | 1,991 | 1,137 | 509 | 1,603 |

On the other hand, the large land-holders cultivate the best farmland of classes I, II, III, and IV (see appendix 1), mainly with crops of sugarcane and coffee destined for export, and by the same token use a great deal of agrichemicals, with which they affect the quality of the earth on a large scale.

As a consequence, the nation’s farmland has suffered significant decline in recent years, such that 64% of the farmland is considered class V, VI, or VII, which means it should only be devoted to permanent crops such as forests, fruit trees, or coffee, which prevent erosion. With erosion, there has been a loss of the capacity to absorb water, as a result of which the availability of same for human consumption and even for these same productive activities has been impacted.

Table 3.3 Surface area by sector (2006)

| Market | Current (hectares) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 381,941 | 23.6 |

| Coffee | 152,339 | 9.4 |

| Sugarcane | 64,606 | 3.9 |

| Agro-industry | 7,231 | 0.4 |

| Green vegetables | 12,665 | 0.7 |

| Fruit | 13,385 | 0.8 |

| Ranching | ||

| Unused | ||

| Forest | ||

| (Natural forests, lands of classes VII and VIII, mangrove forests) | 359,144 | 22.2 |

| Mechanized class I-II | 95,095 | 5.8 |

| Other uses | 291,336 | 18 |

| Total | 1,619,930 | 100 |

Farm Labor Movements and Agrarian Reform

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, an agrarian oligarchy consolidated, maintaining high levels of exclusion and exploitation of the farm-working class. This inequality created organizing tendencies, movements, and uprisings among farm workers, with the goal of ending the levels of rural poverty, the exclusion of rural populations, and above all, a distribution of land that ensures access to it for most farmers. The uprising of 1932 was in this context, including the participation of a majority of farmers and indigenous peoples and, to a lesser degree, of other workers, resulting in the killing of at least 32,000 people and the consolidation of military power.

In the 1960s, there was a resurgence of an organized movement as much in the city as the countryside: labor unions and organizations of teachers, students, and others. In rural areas, there was an important movement of agricultural workers and farmers, with the most relevant expressions being the Christian Federation of Salvadoran Farmers (CFSF) and the Union of Farm Workers (UFW), plus other agrarian groups that developed throughout the east, center, and west of the country, whose agenda was focused on: access to land, to credit, cheap agricultural supplies, free organization or unionization, better pay, improvements to food, and a reduction in working hours.

As popular discontent and the demands of farm-labor organizations for reform became increasingly energetic, the U.S. government designed an agrarian policy from a standpoint of counter-insurgency in Latin America in order to avoid these countries from becoming “satellites of international communism” (per the Santa Fe Report, 1980). This U.S.-designed reform had as its goal the stripping of sympathy and rallying points from revolutionary movements, headed by the organizations that would go on to form the Farabundo Martí Front for National Liberation (FMLN). These reforms were accompanied by the persecution and murder of leaders that the government suspected were “subversive.”

The design of these reforms was made up of three phases. Phase I (Decree 154) consisted of transferring lands expropriated from owners of more than 715 blocks, organizing cooperatives, and financial assisstance. In this first phase, it was recognized that in the first years of its implementation until 1989, it affected an area of 228,135 hectares, distributed in 333 cooperative associations, which in total were made up of 36,558 direct beneficiaries.

Phase II sought to resistribute the land of those owners of 214 to 714 blocks. This phase has still not yet been completed; however, a phase III has nonetheless begun (Decree 207), in which owners of less than 143 blocks are obligated to transfer those parecels that they previously rented, prioritizing individual ownership of at most ten blocks, which resulted in a significant increase in small farms. According to the World Bank, under this phase a total of 80,000 hectares were distributed to 84,000 beneficiaries (see table 3.4).

Thus phases I and III cover between 15 and 20% of the total agricultural lands, while the remaining 85% were not, and if we include lands from the Land Transfer Program from the peace accords the total is 23%. This 77% of land that is in the hands of landowners show that there remains a high concentration of land in few hands. Many land owners, to guarantee that their lands were not transferred, divided them and put them under the names of others people, be they family members or close friends. For their part, Chávez asserts that:

The failure of the agrarian reforms may be attributed to three main reasons: first, the reforms were focused on reducing social discontent, which is to say, that it was a counter-insurgent reform, which beyond seeking to transfer lands to farmers had an underpinning of political stability. Second, the political nature of the initiative did not respond to the needs of the rural population, since it was an imposition by the State. Finally, the reforms created a conflict of interest between the economically-dominant class and the State, and so could not be completed.

Table 3.4. Redistribution of land under the agrarian reforms.

| Phase | Hectares | Beneficiaries |

|---|---|---|

| I | 215,000 | 37,000 |

| III | 80,000 | 47,000 |

| Total | 295,000 | 84,000 |

The Peace Accords

Peace negotiations between the government of El Salvador and the FMLN between 1990-1992 coincided with the start of the implementation of the neoliberal model, pushed by the first government of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (“Arena”) under the direction of the World Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Interamerican Development Bank (IDB). This created the tension that since then had characterized the peace process in El Salvador, that is to say, the contradiction generated in the setting of a neoliberal model and the needs of a lasting peace that eliminated the causes of the war lays the foundation for development with social justice (something that is in itself a contradiction).

As part of the Peace Accords signed in 1992 between the FMLN and the government of Alfredo Cristiani, the agrarian issue was considered, and the government agreed to complete the mandates set forth in articles 104, 105, and 267 of the Constitution of the Republic in regards to land ownership, which required the transfer of lands in excess of 245 hectares per owner via the Program of Land Transfer, known as PTT,4 and to actively provide credit and technical assistance to new land-owners.

To address the problem of land, the Peace Accords established three actions: (1) distribute lands to farmers without it, giving preference to the ex-combatants of both sides; (2) provide a satisfactory legal solution to land ownership in conflict zones for the benefit of land-holders; and (3) transfer lands occupied by farmworkers’ organizations in other geographical areas, outside of the conflict zones, at the time of the treaty. This treaty would be known later as the July 3 Accord.

As a result of the implementation of these actions, and according to the World Bank, under the auspices of the PTT implemented between approximately 1992 and 1995, a total of 78,000 hectares were distributed to a total of 30,000 beneficiaries, and 1,473 hectares to a total of 1,000 beneficiaries (see table 3.5).

It is important to note that the beneficiaries of the PTT received land pro indiviso,5 which created possibilities for the development of a significant process of farmworker organization; however, for various reasons, this opportunity was not taken, and moreover this pro indiviso was ended under the auspices of a program financed by the IDB, which resulted in taking by individual ownership, and the end of the story of mini-groups in the country.

Table 3.5. Program of Land Transfer (PTT), 1992-1995

| Program | Hectares | Beneficiaries |

|---|---|---|

| PTT | 78,000 | 30,000 |

| July 3 Accord | 1,473 | 1,000 |

| Total | 79,473 | 31,000 |

Nonetheless, despite the data offered by the World Bank, the Farmworkers Democratic Alliance (FDA) believes that the PTT and July 3 Accord have not been wholly complied with, above all with respect to land holdings exceeding 245 hectares, to the extent these were no distributed according to treaty, since the owners divided the excess among relatives to ensure that they were not affected. By the same token, the FDA maintains that the information on 361 landowners that have more than 350 blocks (245 hectares) has disappeared from the archives of the property registry.

The Neoliberal Model and its Impact on the Cooperative Movement

In the 1980s, after the global economic crisis, successive governments with the help of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank imposed the Economic Stabilization Programs (ESP) and the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP).

The supposed foundation for implementing these programs was at its base the neoliberal doctrine that part of the cause of the economic crisis was excessive state intervention in economic activity. Which is to say, a state that has a monopoly on the production and sale of services, with the ability to control the market, as much internal as external.

In this context, the economic programs impemented by the Arena governments starting in 1989, had as their objective the modification of economic structure and the creation of conditions for re-entering the global economy by setting out a new economic model based on non-traditional exports, mainly industrial, and reducing protectionism to re-insert the economy in the global marketplace. In other words, the objective was to configure a new model of accumulation of capital, oriented primarily towards the most profitable sectors of the economy, which also privileged the market as the distributor of resources.

With this goal, actions were completed such as the privatization of most public companies, including in banking, and the liberalization of the economy, meaning the liberalization of exterior trade, of prices, etc.

With respect to the agricultural sector, a series of measures were adopted that without any doubt caused its later deterioration, and in a few years converted it to one of the least dynamic sectors of the national economy, which primarily affected the production of basic grains.

Furthermore, the privatization of the banks with the exception of the Agricultural Development Bank and the Mortgage Bank, saw the reduction in credit for agricultural production, particularly for small and medium-sized farmers. According to the agricultural census by the Ministery of Agriculture and Income in December 2009, only 40,578 producers obtained loans, which is 10% of the total number.

At the same time, the State’s monopoly on exports of coffee and sugar was eliminated, the Regulatory Institute of Supply was closed, which was the institution that would buy basic grains from farmers at better prices; in its place was created the Agricultural Products Fund.

Exterior trade was liberalized, and as a result the import of goods and services, including agricultural products, creating private monopolies with the ability to control the commercialization of agricultural tools, including seeds. In addition, this commercial opening has meant an increase in the import of agricultural products at low prices, whose quantities have been increased by anti-competitive practices such as dumping, impacting the production capacities and commercialization of local products.

These measures have had very large consequences for the agricultural sector, the loss of confidence among farmworkers reinforced trends of immigration like those experienced in the 1960s and 1970s with the implementation of the ISI model and in the 1980s with the civil war.

In sum, with the end of the war in the 1990s, neoliberal policies favored large businesses and commercial agriculture for import and export, and they disincentivized subsistence production and de-stimulated the production of basic grains and other foodstuffs for the internal market, as a result of which the dependence on imports to satisfy internal demand increased.

In this context, the total demand in El Salvador for basic grains is covered in part by imports and in part by local production. In the case of maise, for example, 43% of the total demand is satisfied by imports and 56.9% by internal production; imports of beans, for another example, cover 20.8% of demand and the rest, 79.1%, by internal production; with rice, imports cover 79% of total demand.

With that commercial opening and later the signing of the Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), imports were allowed of basic foodstuffs for daily consumption, and consequently, the national agricultural sector was gradually dismanteled, and year by year there has been a larger dependence on foodstuffs brought from beyond El Salvador’s borders.

Access to food in El Salvador has been improved by a greater importation of foodstuffs, which has resulted in deterioration in Salvadoran lands and an increase in the cost of the Basic Food Package (BFP).6 The situation is more critical in the rural parts of the country, where wages do not reach the level needed to supply sufficient foods to maintain a household.

In the last 22 years we have seen a growing process of deterioration in rural conditions, the loss of productivity, and equally the organizing abilities of farmworkers. The impact that all these measures had on the cooperative agricultural sector is illustrative. In the 1990s there were 2,170 agricultural cooperatives, meaning a productive unit that belongs to a certain number of farmers, primarily dedicated to growing basic grains, although some of these units were dedicated to coffee, sugarcane, and other types of crops. Around 1,700 cooperatives belong to the non-reformed sector that was organized in the context of the Alliance for Progress with guidance from the American Institute for the Development of Free Syndicalism (AIDFS), the United States Embassay, and the International Development Agency (IDA), with support from the Salvadoran government, the Communal Salvadoran Union (CSU), and the Catholic Church, which promoted cooperative organization with conservative ends.

Of these 2,170 cooperatives, 470 (21.7%) belonged to federations from the reformed sector, which refers to those cooperatives created in the setting of agrarian reform. For its part, the Ministry of Agriculture and Ranching registered 35 federations, but now only 19 are active, with the other 16 disappearing between 1996 and 1999, precisely in the period of the condonation of banking and agrarian debt and the intensification of the process of parcelization of cooperatives.

Between 1990 and 2010, there was a growing process of weakening in the cooperative sector, the result of policies compelled by neoliberalism. In this context we see: (a) of 470 agricultural associations, 117 cooperatives in the reformed sector no longer exist; (b) of 35 federations of agricultural collectives, 16 no longer exist; (c) of five agricultural confederations, three no longer exist.

A good example of this weakening of farmworkers’ organization may be found in the Confederation of Federations of Agricultural Reform in El Salvador (Confras7), which was composed of 320 cooperatives in 1992, had shrunk to 192 by 1998, and in 2008 was only made up of 129 cooperatives. Its membership went from 19,000 people in 1992 to 15,000 in 1998 and 7,627 in 2008. Similarly, the Salvadoran Federation of Agriculture Reform Cooperatives, one of the main federations in the country, shrunk in terms of unions [within it] from 220 in 1992 to 127 in 2006.

An important loss for the farmworkers’ movement was the disappearance of the Democratic Farmworkers Alliance (DFA), founded in 1989 and completly dissolved in 2002. The DFA had among its great accomplishments the recouperation of land in July 1991 which resulted in the July 3 Accords (part of the Peace Accords), by which former president Cristiani agreed to assign lands to those farmworkers that had taken them under Article 105 of the Political Constitution, which defines the amount of land that a person or legal entity may possess.

In the present day, the farmworker has less weight numerically and politically. In 1992, the rural population represented almost 50% of the total, but decreased to 37% in 2007, a result of the loss of importance had by the agricultural sector in the national economy, itself a product of policies that led to its destruction, such that this sector ceased to be the main source of capital accumulation in the neoliberal context, which in turn caused thousands of farmworkers to emigrate to the cities or abroad, and that some large hacienda owners to move to the service sector of the economy.

Table 3.6. Rural population in El Salvador

| Census Year | Total | Urban Population | Rural Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 1,434,461 | 545,095 (38%) | 889,365 (62%) |

| 1950 | 1,855,917 | 668,130 (36%) | 1,187,786 (64%) |

| 1961 | 2,510,984 | 97,8838 (39%) | 1,531,700 (61%) |

| 1971 | 3,556,648 | 1,422,659 (40%) | 2,133,988 (60%) |

| 1992 | 5,118,599 | 2,133,988 (50.4%) | 2,538,825 (49.6%) |

| 2007 | 5,744,113 | 3,561,350 (62%) | 2,142,554 (37.3%) |

In 15 years of the neoliberal model, from 1992 to 2007, a total of 396,270 farmworkers were expelled from the countryside to the city, ceasing to be farm- or argricultural workers.

The New Rurality

In El Salvador and its neighboring countries, transnationals conceive of the rural world simply as a space to realize their goals of capitalist income. Transnational capital tries to descibe the rural zone on the one hand as a nucleus of income around which state support is focused on development and the population and all economic and social activities revolve.

In El Salvador, as in the rest of Latin America, these nucleii are understood as socioeconomic processes created around a principal activity; this new rurality, from the viewpoint of transnational capital, rests especially on infrastructure projects such as hydroelectric dams, international electrical connections, highways, dry canals, ports, and airports; exploitation of gold, silver, and petroleum; tourist projects in the Pacific and north of the country; etc. Within the vision of this imposition of external interests and values, this vision means for communities a high degree of de-territorialization and often the displacement of thousands of rural families.

Rural communities have a different vision; land is not merchandise, land is life and rurality is conceived as a right to land and territory. It is about reorganizing territory according to needs, culture, and the decisions of the organized rural population themselves and their plans.

In this sense, the fight for access to land in El Salvador, which has been a rallying point since the end of the 19th century, has become current. It is a vision of recovering the countryside and means of production in keeping with nature, oriented primarily towards ensuring food for human reproduction and a life of dignity, outside of any logic of the market. Further, the fight for land in the present day also means taking actions that will lead to food sovereignty.

According to Farmers’ Way, food sovereignty includes: (1) prioritizing local agricultural production to feed the population, the access to land, water, seeds, and credit for farmers and those without land–from this comes the need for agrarian reforms–, the fight against genetically modified organisms for free access to seeds, and keeping water as a public good, shared in a sustainable way; (2) the right of farmers to produce food and the right of consumer to be able to decide what they want to consume and how it is produced; (3) the right of nations to protect themselves from agricultural and food imports; (4) the participation of the people in defining agricultural policy; and (5) the recognition of the rights of farmers that play an essential role in agricultural and food production.

Conclusions

It is necessary to state some ideas that should be considered in the debate on the importance of agriculture for human reproduction and for a new relationship with nature. Up to now, the history of the rural sector has been a struggle of two visions for the development of the countryside. On one side is capital, which sees agricultural production, including of foodstuffs, from a logic of capital accumulation, in which all agricultural goods take on the character of merchandise, and as such are accessible to the extent that the population has the resources to buy them. This logic has allowed high levels of speculation and the reorientation of food as a raw material in the production of goods that are inedible for human beings. In this logic of capital, there is currently talk of the “green economy,” which assumes a series of actions for the purposes of making the economy green, but what is sought in reality is greater control of natural resources that would provide capitalists a greater proportion of land and force the implementation of new technologies for increasing productivity with the sole aim of generating more profits.

On the other side there is the perspective of the indigenous peoples and farmworkers, who see agricultural production as a source of life and the access to food as a fundamental human right, in a permanent effort to reconnect with ancestral forms of production and to confront the capitalist methods of production and consumption.

The above has set out important processes in the heart of rural communities of conflict and organization, albeit incipient and dispersed, which currently does not allow them to be considered as new sources of large-scale action. Instead, they seek to band together to defend their territories. That is the case with El Salvador, where the fight for food sovereignty has strengthened in the last several years insofar as it expresses a true response to the crises of the environment and of food created by capital.

-

Translator’s note: Haciendas are large estates similar to plantations in the American South, although not necessarily limited to agriculture; they could instead focus on some combination of agriculture, mining, and manufacturing. ↩︎

-

Translator’s note: This quote is from a 1997 analysis by the Salvadoran Program for Research on Development and the Environment. ↩︎

-

Translator’s note: The term I’ve here rendered as “block” (Spanish manzana) can refer to an apple (the fruit), and is also used in some cases to refer to a city block (hence my translation). But here, it is a specific unit of measurement used in various Central and South American countries (the size of which can vary from one country to another). Such a “block” in El Salvador is 0.7 hectares. See SIZES, manzana, last accessed Feb. 16, 2024. ↩︎

-

Translator’s note: The abbreviation “PTT” comes from the Spanish name, Programa de Transferencia de Tierras. ↩︎

-

Authors’ note: This is a legal term, meaning that farmers would get land but it would not be proportioned among them, with the result that they were unable to sell it. ↩︎

-

Translator’s note: What I’ve translated as “Basic Food Package” (Spanish Canasta Básica Alimentaria) is a statistic prepared by El Salvador’s Central Reserve Bank, which compiles the monthly prices for set amounts of basic foods per person in urban and rural areas of the country. It is intended “[to] represent the minimum caloric requirements needed by an individual to perform a job” (per the Salvadoran National Office of Statistics and Censes). ↩︎

-

Translator’s note: This abbreviation is from the organization’s Spanish name, Confederación de Federactiones de la Reforma Agraria de El Salvador. ↩︎

-

Translator’s note: Thus in original. This seems to be an error (given that the urban and rural numbers do not add up to the total), but it is not clear on whose part. Subtracting the rural population from the total yields 979,284. ↩︎